Julius Caesar led Roman forces to victory in the decisive battle of the conquest of Gaul at Alesia. Having pursued the Gauls to a fortified city, Caesar first surrounded the city with a wall (to keep the Gauls trapped in Alesia) and then a second wall (to keep Roman forces protected from a relief army). Having completed these and other siegeworks, Caesar began the process of starving a surrender out of Alesia. Vercingetorix, the commander in Alesia, forced his non-combatants (women, children and elderly men) out of the city and into the no-man’s land between the city wall and the newly built interior Roman wall. The cruel decision had two aims- first to stretch the supply of food for the defenders, and second to convince the Romans to stretch their own limited supplies.

Julius Caesar led Roman forces to victory in the decisive battle of the conquest of Gaul at Alesia. Having pursued the Gauls to a fortified city, Caesar first surrounded the city with a wall (to keep the Gauls trapped in Alesia) and then a second wall (to keep Roman forces protected from a relief army). Having completed these and other siegeworks, Caesar began the process of starving a surrender out of Alesia. Vercingetorix, the commander in Alesia, forced his non-combatants (women, children and elderly men) out of the city and into the no-man’s land between the city wall and the newly built interior Roman wall. The cruel decision had two aims- first to stretch the supply of food for the defenders, and second to convince the Romans to stretch their own limited supplies.

Vercingetorix, who had previously been running a guerrilla-style campaign attacking Roman supply lines, underestimated Caesar. Caesar was only willing to leave a single way out for his opponents. Caesar refused the refugees, and when a huge Gallic relief army attacked the outer Roman wall while Vercingetorix’s forces assaulted the inner wall, Caesar defeated both forces. After multiple failed assaults, the relief army withdrew, and Vercingetorix surrendered.

Why the trip down historical memory lane? In a Vercingetorix-like move, a bill in Oklahoma proposes to cast more than 1,400 Oklahoma students out of the state’s personal use tax credit program. Oklahoma’s potentially revolutionary refundable personal use tax credit inspired your humble author to write a study on the promise of the approach. Oklahoma has by far the most potent personal use tax credit, but improvement opportunities include eliminating or lifting the statewide cap on funding and the limiting of participation to accredited private schools. The accreditation requirement puts any new private school in the position of competing with established private schools whose students can access the credit for years as they seek accreditation.

As noted in the study:

“Oklahoma covers 68,577 square miles in land area, so 160 participating private schools is only one for every 480 square miles in the state. The state’s population of course is not distributed evenly throughout the state, but for context: Oklahoma has more than 1,700 public schools. The relative scarcity of private schools in the state makes the onboarding of new private schools crucial to the success of the program. Educators could create new private schools, especially in areas in which demand exceeds supply. Unfortunately, lawmakers did not design the Oklahoma Parental Choice Tax Credit Act in a fashion that recognizes the need for additional private schools.”

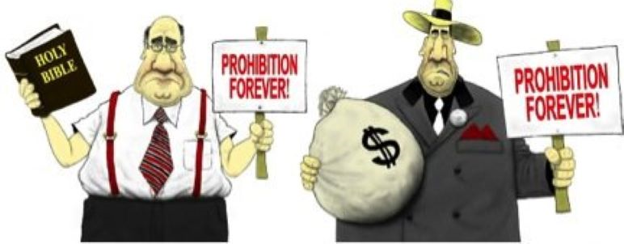

In other words, a requirement for private school accreditation that does not provide an onramp for new school supply looks like a visit from our old nemesis, the Baptist and Bootlegger coalition.

A reasonable approach adopted by multiple states to address this issue allows new schools to participate in choice programs while in the process of seeking accreditation. Unfortunately, legislation currently pending in the Oklahoma legislature would tighten accreditation requirements, eliminate 30 schools with private accreditation from participating, and upend the education of 1,400 students in the process. In short, it fails to address one major shortcoming of the Oklahoma program and makes another one worse. Several school choice and religious liberty groups have communicated their opposition.

The legislation includes a trade: grandfathering credit participants from year to year in return for tightening accreditation. The cap created the possibility that families might not be able to participate from year to year; eliminate the cap, eliminate the problem. While everyone should feel sympathy for families unable to continue participating in the credit because of the cap, the interests of students whose education solutions lie in startup schools stand as no less worthy. In fact, grandfathering will have the effect of casting other students out.

Balancing the demand and supply side of the choice equation will be vital to developing a truly flourishing education space.

Oklahoma lawmakers created the most robust K-12 personal use tax credit in American history last year. It occurred to your humble author that with a couple of tweaks an Oklahoma-style credit could be productively included in the school choice mix of any state to turbo charge the choice mix, so I authored a study about it, including the following bit:

Oklahoma lawmakers created the most robust K-12 personal use tax credit in American history last year. It occurred to your humble author that with a couple of tweaks an Oklahoma-style credit could be productively included in the school choice mix of any state to turbo charge the choice mix, so I authored a study about it, including the following bit:

In 2023, Oklahoma lawmakers passed the most robust personal use education tax credit to date. The Oklahoma Parental Choice Tax Credit provides families sending their children to accredited private schools credits worth between $5,000 and $7,500 (varying by family income with lower-income families receiving larger credits). The law also provides for $1,000 for homeschooling students. Lawmakers designed the credit to be refundable. For example, a family with $5,000 of eligible expenses at an accredited private school but $4,000 in Oklahoma tax liability will still receive a $5,000 credit, with the difference reimbursed to the taxpayer.

Qualifying expenses for the private school credit include tuition and fees, whereas the law covers a broader array of educational expenses under the smaller homeschooling credit. For 2024, the Oklahoma lawmakers capped the private school tax credit program at $150 million, increasing to $200 million in 2025 and then to $250 million in 2026 and beyond.

Assuming a midpoint average between the $5,000 maximum for higher earners and the $7,500 maximum for lower-income families, ($6,250) the private school credit would serve approximately 40,000 students and the homeschool credit as many as another 5,000 students when it reaches the $250 million cap. This represents approximately 6% of the public-school enrollment of Oklahoma in 2022.

At the time of this writing of the study, approximately 160 Oklahoma private schools had registered with the state to participate in the private school credit. Family access depends on the number of participating schools, their proximity to families, and the number of available seats at the grade levels sought by families.

Oklahoma covers 68,577 square miles in land area, so 160 participating private schools is only one for every 480 square miles in the state. The state’s population of course is not distributed evenly throughout the state, but for context: Oklahoma has more than 1,700 public schools. The relative scarcity of private schools in the state makes the onboarding of new private schools crucial to the success of the program. Educators could create new private schools, especially in areas in which demand exceeds supply. Unfortunately, lawmakers did not design the Oklahoma Parental Choice Tax Credit Act in a fashion that recognizes the need for additional private schools.

Step one to improve the Oklahoma Parental Choice Tax Credit: overcome our old nemesis, the Baptist and the Bootlegger coalition. In this instance, it appears that pre-existing accredited private schools in Oklahoma crushed potential competitors by denying them credit access. This could be accomplished by either dropping the accreditation process entirely, or else by allowing private schools seeking accreditation (often a multi-year process) to participate in the program. Assuming Oklahoma lawmakers want rural Oklahomans to participate, special attention should be paid to allow microschools to participate.

Given that public school attendance, private school attendance and homeschooling all satisfy the mandatory attendance requirement of Oklahoma, it is hard to see how private school attendance is 7.5 times more worthy of subsidy than homeschooling. Thus, an expanded list of allowable expenses for items such as tutoring, college tuition, books and other expenses helpful to a la carte education should be pursued. Again, Oklahoma’s bootlegger-accredited private school community will likely object, but the object of our policies should not be to create a parallel monopoly of private schools to subsist on a tame choice policy.

Next there is the funding amount. On the surface, $250 million seems to represent a large amount of money, put into context, it is not sufficient to drive dynamic K–12 change. The goal should be to have a demand-driven education system where teachers can create schools and recruit students who will be reliably funded. This is hardly too much to ask; district and charter schools receive funding in exactly this fashion. Programs funded by appropriation or with caps, however, create waitlists of students, introducing uncertainty in the process of creating new supply.

If Oklahoma parents hit the tax-credit cap in the third year of the program, the credit would educate more students than Oklahoma’s highest-funded school district (Oklahoma City) but would only provide a funding amount equal to approximately 56% of the Oklahoma City district’s budget. It’s a start on the journey, but not the desired destination.

The boldest move would be to eliminate the cap entirely and let ‘er rip. That would be as glorious as the melodious voices thousands of cherubim singing in exultation by my way of thinking. People elected to budgetary positions, burdened as they are by responsibilities and spreadsheets and such, might desire a more incremental approach. (Humbug, grumbles and wacky sassafras) Fortunately, Florida lawmakers provided us with a more incremental approach back in 2013:

In the 2013–2014 state fiscal year and each state fiscal year thereafter, the tax credit cap amount is the tax credit cap amount in the prior state fiscal year. However, in any state fiscal year when the annual tax credit amount for the prior state fiscal year is equal to or greater than 90 percent of the tax credit cap amount applicable to that state fiscal year, the tax credit cap amount shall increase by 25 percent. The Department of Education and Department of Revenue shall publish on their websites information identifying the tax credit cap amount when it is increased pursuant to this subparagraph.

Your mission, should you choose to accept it, is to take a great law and make it awesome. Remember to take competition to heart, then you can start to make it better.

The Oklahoma Statewide Virtual Charter School Board met Tuesday to discuss a vote on whether to approve creation of St. Isidore of Seville Catholic Virtual School. PHOTO: Doug Hoke/The Oklahoman

Editor’s note: For related posts from reimaginED senior writer Lisa Buie, click here and here.

Concerned about conflicting attorney general opinions and the certainty of a lawsuit, members of Oklahoma Statewide Virtual Charter School Board unanimously voted to disapprove the application for what would be the nation’s first religious charter school.

The vote was a procedural move to buy time so board members could gauge the risk of personal liability following their final vote on St. Isidore of Seville Catholic Virtual School. Board members turned down the application on Tuesday after sidestepping the legal issue and instead raising questions about the school’s governance structure, special education plan, how it would prevent government money and private donations from co-mingling and technology.

“Do we have assurance from counsel if we are sued that we would have protection and support from the Attorney General’s Office?” board Chairman Robert Franklin asked during the discussion. “In recent history this board has been sued collectively and individually.”

The board’s counsel, Deputy Attorney General Niki Batt, said board members would receive representation if they were following state law and their actions were in the scope of their board position.

She said Oklahoma law explicitly states that no public money can be applied to support any religion.

That drew concern from board member Scott Strawn, who said, “Candidly, it feels like – intentional or not – that we’re basically being told make a decision against the advice of the attorney general and you may or may not have immunity.”

Heightening the tension are two conflicting legal opinions and statements the governor made about them.

Former Attorney General John O’Connor issued an opinion in December as his final official act that came as the statewide virtual charter school authorizing board was set to decide on the application for St. Isidore of Seville Catholic Virtual School, which the Archdiocese of Oklahoma City and the Diocese of Tulsa want to open to serve students in rural areas without a traditional Catholic school and to expand course offerings for students who already attend Catholic schools.

O’Connor said in his opinion that the state’s ban on publicly funded charter schools operated by sectarian and religious groups could violate the U.S. Constitution’s First Amendment and should not be enforced.

His successor, Gentner Drummond, withdrew O’Connor’s opinion and argued that it was based on precedent for private schools. Drummond said that state law defines, and the attorney general has previously recognized, charter schools as public schools, and that allowing the state to sponsor a religious school would create “a slippery slope” to use religious liberty to justify state-sponsored religion.

The clash promoted Gov. Kevin Stitt to weigh in by releasing a letter disagreeing with Drummond’s withdrawal of his predecessor’s opinion.

“You contend that the United States and the Oklahoma Constitutions permit, and indeed require, the state to discriminate against religious organizations seeking authorization to operate charter schools,” Stitt’s letter said. “In fact, the opposite is true.”

The letter continued, “These prohibitions run afoul of the non-discrimination principle articulated by the U.S. Supreme Court in recent cases.”

During Tuesday’s board meeting, state schools Superintendent Ryan Walters said he and the Oklahoma Department of Education would provide support to board members who approve the school’s application, thought it was unclear if that include legal representation.

Brett Farley, executive director of the Catholic Conference of Oklahoma, told The Oklahoman that the vote came as no surprise.

"This is fairly normal for their application process," Farley said. "It gives us more time to address their concerns, and so we'll do that and come back and present those and see where we go."

By turning down the application, members reset the clock on when a final vote must be taken. The rules allow applicants who are initially disapproved to make changes and resubmit their applications for a vote within 30 days. Had the board simply postponed Tuesday’s vote, the deadline for final approval would have been April 29.

You can watch a recording of the meeting here starting at the 49:22-minute mark.