PORT RICHEY, Fla. – Like many students in Florida, Desiree Schmidt had multiple options when it was time to decide on high school. She chose to stick with Dayspring Academy, the charter school she had attended since kindergarten, and to enroll in its “early college” program. Neither Desiree’s mom, a hairdresser, nor her dad, an electrician, had gone to college. So they loved a program where Desiree could earn a diploma and a two-year degree at the same time.

It wasn’t easy. Desiree, now 16, said there were times early in high school that the intensity of college prep had her tearing up in the principal’s office. Dayspring, though, devotes extra resources to counselors, tutors and other supports, and its staff continued to nudge and encourage. Now Desire is a confident junior, taking five college courses and looking toward a career in the medical field.

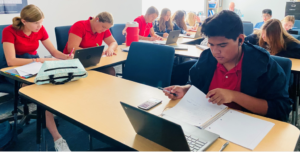

“Dayspring has prepared me for this, 100 percent,” she said while studying on her laptop in Dayspring’s break room. Early college “teaches you to get yourself together.”

Early college high school may be the best choice option you’ve never heard of. The academic and financial benefits seem obvious. The evidence to date is encouraging. And yet, outside of a few states like Texas and North Carolina, the model is still a bit under the radar.

The popularity of the Dayspring program suggests it’s just a matter of time.

The K-12 school 40 miles north of Tampa opened a $5.5 million building this fall to house its Dayspring Early College Academy. The program has 199 students this year and expects to have 300 by 2023. Since students already enrolled in Dayspring get first dibs on the high school slots, there aren’t many left for others. This year, 425 students outside of Dayspring applied for the 20 slots that remained.

“There’s a pent-up demand in the community for rigorous pathways that lead to degrees,” said Dayspring co-founder John Legg.

The Dayspring academy underscores multiple changes on Florida’s increasingly choice-driven education landscape. It’s obvious more choices are sprouting, but it’s also easy to find parents gravitating to those with academic heft. At the same time, Dayspring is another example of lines blurring between sectors and silos – in this case, between high school and college.

Florida has been a leader in this space for two decades. In the late 1990s, it broadened access to college-caliber Advanced Placement classes so more low-income students and students of color could participate. Today, Florida is No. 2 in America in the percentage of graduating seniors who have passed AP exams. The number of Florida students taking dual enrollment classes – college classes that give them both high school and college credits – has also risen sharply. They now total more than 80,000 each year.

Early college, though, is dual enrollment on steroids. Rather than take a few dual enrollment courses, students in early college high schools aim to graduate with a diploma and a degree. Juniors and seniors at Dayspring take some of those college classes on their campus and others at the state college the school partners with. They not only prep for college, they do college.

Junior Micah Faltraco said the adjustment was tough at first. Professors didn’t tolerate late or shoddy work. “But I realized I could do it,” said Micah, who’s planning to study psychology in college. “Having an AA will give me … a head start on life.”

There isn’t solid data just yet on the number of early college programs and the students enrolled in them. Kristina Zeiser, a senior researcher at the American Institutes for Research, is in the process of collecting that. She said via email that the most recent estimate, from 2014, put the number of early college high schools nationwide at more than 280. But several states have introduced early college programs that fall within traditional high schools. The proliferations of those programs, Zeiser wrote, has made it difficult to get a good handle on total programs and enrollment.

In Florida, it’s befuddling why there isn’t more early college.

There are a handful of “collegiate high schools,” a related model that also aims for simultaneous diplomas and degrees. (Full disclosure: My son attends one.) But they’re located on college campuses and tend to have more restrictive eligibility requirements.

Legg said early college could be having a tougher time taking root because it’s in that fault line between K-12 and higher ed. It could be the modestly higher cost is a deterrent. It’s also possible, he said, the concept suffers from a misperception that it’s for more affluent students.

“I call it the soft bigotry of perceived elitism,” said Legg, a former state senator who chaired the Senate Education Committee. (Legg is also on the board of directors for Step Up For Students, the nonprofit that hosts this blog.) The truth, Legg continued, is “early college is a customized approach for first-generation-in-college students and particularly low-income students to gain the skills they need for long-term success.”

A growing body of evidence shows early college is paying off.

For years, the American Institutes for Research has tracked more than 1,000 early college students in five states who won admissions lotteries to get into the programs, and 1,400 who applied but didn’t win. The former, it found, were more likely to enroll in college and earn degrees. Six years after graduating from high school, 45% of them had earned degrees, compared to 34% for the control group. With bachelor’s degrees, the corresponding rates were 30% and 25%. Importantly, low-income students and students of color had outcomes as positive as other groups.

AIR also found a big return on investment. Early college high schools cost about $1,000 more per year per student, researchers calculated, because of additional cost for college advising, “summer bridge” programs and other supports. For context, Florida spends about $11,000 per student per year. But given adults with college degrees tend to earn more money, pay more taxes and require less in social services, the study concluded the return on investment is 15 to 1.

Dayspring students cite more immediate benefits.

Junior Ezriah Rooker said he didn’t hesitate to sign up for the academy because “two years of free college!” But the self-discipline it fostered has been invaluable.

“There was a whole lifestyle change,” said Ezriah, whose dad is an air conditioning contractor and whose mom is an auditor for an insurance company. “I’m a notoriously lazy person. But I’m keeping up with a schedule, staying consistent, checking my calendar. I had to sort that out on my own.”

Desiree’s mother, Danielle Schmidt, said she initially did not want her daughter to attend the early college academy, thinking a traditional high school would be better. “I thought she’d be weird,” Schmidt joked. “I didn’t want her to be this isolated kid, and then she’d get to college and be around 10,000 kids.”

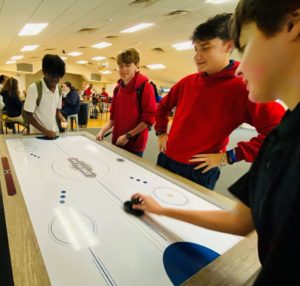

Thankfully, she said, Desiree insisted. Dayspring is smaller, but it has most of the trappings and traditions of a typical high school. More importantly, Schmidt said, the school is guiding Desiree towards that self-reliance she’ll need to succeed in college and beyond.

In Florida, recent policy changes may open the door for more early college. Legislation passed this year requires every state college to work with school districts to establish such programs.

It also says charter schools can contract with colleges to do the same.

“The Legislature pitched one right down the center of home plate,” Legg said. “But it’s up to state colleges and districts to hit it.”

If they don’t, he said, charter schools like Dayspring will.