Microschools have been having a moment, garnering positive headlines in the Christian Science Monitor, Wall Street Journal, Washington Post and other mainstream outlets. They’re one of the hottest topics on social media and the education conference circuit.

So it’s no surprise the inevitable backlash is brewing.

Before we get into it, I’d like to make one stipulation. The term “microschools” defies tidy definitions.

Often, but not always, microschools are smaller than typical learning environments. Often, but not always, they operate outside the aegis of the public school system. Sometimes, but not always, they rely on adults who don’t hold traditional teaching credentials. Sometimes, but not always, they blur the lines between schooling and homeschooling, hosting students around living room tables or on farms or in the woods.

Two different people may use the term microschool and have completely different learning environments in mind. Neither would necessarily be wrong.

Now for the backlash, via education blogger Peter Greene.

When someone asks hard critiques like “This voucher you’re offering me won’t cover the cost of any private school” or “When this voucher program guts public school funding, families in our rural area will have no choices at all” then microschools are the handy choicer answer.

Can’t get your kid into a nice private school with your voucher? Well, you can still pool resources with a couple of neighbors, buy some hardware, license some software, and start your own microschool! Microschools allow choicers to argue that nobody will be left behind in a choice landscape, that vouchers will not simply be an education entitlement for the wealthy. (Spoiler alert: the wealthy will not be pulling their children out of private schools so they can microschool instead).

In other words, microschools do not solve any educational problems. They solve a policy argument problem. They do not offer new and better ways to educate children. They offer new ways to argue in favor of vouchers. Well, all that and they also offer a way for edupreneurs to cash in on the education privatization movement.

Greene is right about one thing. Often, but not always, microschools aren’t competing with elite private schools. It’s a safe bet that most parents shelling out upwards of $30,000 a year for tuition are not about to abandon their exclusive cloisters for a repurposed farmhouse that charges a few hundred bucks per month. Recent reports by the VELA Education Fund on community-created learning environments (which sometimes, but not always, take the form of microschools) and the National Microschooling Center suggest that the typical microschool family is decidedly middle class. These are families who could never contemplate the likes Andover or Gulliver Prep. They might be able to scrape together modest tuition payments, but an $8,000-per-year scholarship could make a big difference in what they can afford.

I’m on the record as a pre-pandemic microschool enthusiast and spent time during the pandemic studying learning pods (which often, but not always, shared many features with microschools). So, I’d like to offer a response to Greene’s question, which recalls the technological skepticism of Neil Postman: What is the problem to which microschools are the solution? And whose problem is it?

For pandemic pods, the answer was simple. Schools shut down, and families needed a place their kids could go.

But many families discovered other benefits they weren’t getting in conventional schools. Teachers could be more flexible with their time, and therefore, more responsive to the needs of their students. Students enjoyed more humane learning environments in big and small ways. Children with disabilities received more individual attention. Students could freely grab a snack when they wanted. Community assets, from the neighbor with a knack for carpentry to the museums and community groups previously confined to afterschool programs, could play a more central part in the schooling experience. Adults from more diverse backgrounds, like parents or community volunteers who loved working with kids but lacked a teaching certificate, found new opportunities to share their passions. And the small size allowed for a far wider array of diverse options catering to families’ unique preferences than were typically possible.

Many parents abandoned their podding experiences once schools reopened. Conventional schools still offered countless advantages (a large and diverse group of peers, guaranteed childcare outside the home, reliable special education services, no out-of-pocket costs).

But other families latched on to the growing array of microschools that, at least for the educators who created them or the families who used them, solve any number of the problems plaguing public education: youth mental health is in crisis, teacher morale is flagging, voluntary community associations are desiccated, students are often disengaged if they’re showing up at all, bonds of trust between schools and families are fraying.

It takes a special kind of cynic to imagine the current blossoming of small learning environments where teachers are free to realize their peculiar vision for what learning could look like and partner with families to make it happen is the brainchild of a few voucher advocates. Notably, most of the learning environments catalogued by Vela say they don’t access public funding at all.

And it’s no surprise legions of researchers, journalists, advocates and program officers at education foundations have all latched on to microschools at the same time. They see previous education reform fads (teacher evaluations, personalized learning) sucking wind. They’re peering desperately for beams of light amid the post-pandemic gloom. And when they actually visit microschools or talk to educators who work in them, they see what I’ve seen: The kids are happy. The teachers are energized. Families and community groups, often sidelined in schools, are pulled into the center of the learning experience. If you ask a student what they’re doing and why, they’ll tell you, often enthusiastically. These are things we should hope to find in any learning environment. The fact that they stand out underscores the extent of the current malaise.

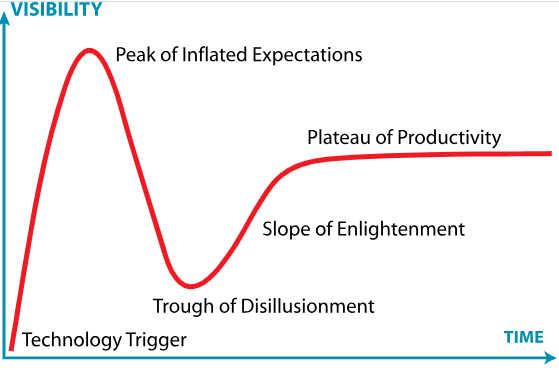

If microschools are following Gartner’s hype cycle, they’re probably coasting somewhere between the peak of inflated expectations and the trough of disillusionment.

To reach the plateau of productivity, they’re going to have to grapple with questions about financial stability and methods for reporting student outcomes. They’ll need to devise new ways to provide special education services, transportation, and other essential infrastructure that ensures they’re accessible to all students.

But I’m willing to bet that anyone who actually visited these learning environments, or spoke to the educators who worked there, would come away with their cynicism punctured and a belief that these bottom-up efforts are getting so much attention precisely because they’re positing novel solutions to countless different problems facing young people and public education.

Thanks for this insight, Travis. I agree with you that the microschool movement as a whole is probably headed for a trough of disillusionment, but I’d like to put a different spin on this. While Gartner’s hype cycle is applied to an entire market, we need to remind ourselves that markets are simply trends of behavior among individual actors. For a handful of us who were involved with microschool before the pandemic, we’ve already experienced the trough of disillusionment and are quickly moving up the slope of enlightenment with the things we’ve learned over the years. We’re now building tools and resources to support microschool innovators in both the learning model and the business model aspects of their microschools. This isn’t about trying to create a flash-in-the-pan moment, but to help bring authentic choice to people in how their children are able to learn.