Editor’s note: On this Fourth of July, redefinED is republishing a post that first appeared in May 2016 about a California school, birthed from years of dissatisfaction with the public school system, that struck a blow for education freedom.

If the American left had fully championed school choice decades ago, we may be celebrating what happened in 1972 in Blythe, Calif., as the spark of a movement.

That spring, the Mexican-American community’s frustration with the public school system boiled over, spurring creation of a scrappy “freedom school” that became Escuela de la Raza Unida, which still exists today.

This lost story from a remote desert town is steeped in the progressive politics of another era.

In Chicano Pride. In empowering the “poor.”

Even in Cesar Chavez and the United Farm Workers.

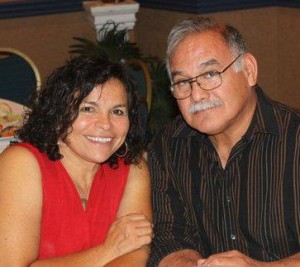

“We were ahead of the curve,” said Carmela Garnica, who has led the school with her husband, Rigoberto Garnica, since the beginning.

Hispanic support for school choice runs strong. But if there is anybody who has chronicled that history, even Hispanic school choice leaders are unaware. Perhaps the story of Escuela de la Raza Unida can inspire the deep dive that this subject deserves.

The school sprang from years of dissatisfaction. The fuse-lighter was an allegation that the principal of the public middle school in Blythe manhandled a female honor roll student, apparently for showing a politically provocative film to a Hispanic student group. But parents had complained about other issues for years. They wanted diversity in the nearly all-Anglo teaching corps. They wanted history lessons that acknowledged contributions of Native Americans and Mexican Americans.

Students picketed the public schools for weeks. In the meantime, the community rallied to create an on-the-fly school where everybody pitched in to teach, cook, clean – whatever they could do. Initially, they met at a local park, according to newspaper articles and “A Choice For Our Children,” a 1997 book by California school choice supporter Alan Bonsteel. At some point, the dissidents decided to rent space for classes, a tiny former post office that could hold 50 students.

They never left.

Escuela de la Raza Unida began as a K-12 private school, and Garnica says it would have preferred to stay that way. But California doesn’t have vouchers or tax credit scholarships, despite multiple attempts at the ballot, including this liberal-led campaign in the late 1970s. Over the years, the school had to shift its mission to best match community needs with available funding.

Now it focuses on early learning and after school care, with other services thrown in. It helps adults translate documents in English, advocates for special education services, offers Mariachi lessons for young musicians. It also established one of the country’s first Chicano-owned educational radio stations.

Garnica said supporters are considering whether to go the charter school route. It could then serve older students, and emphasize career and technical education.

The freedom of a private school would be preferable to the regulatory constraints of a charter, Garnica said. But until the left embraces full choice, including private options, the community of Blythe will have to make do.

“If you’re a wealthy person, you can pay for private education. But if you’re low-income you can’t,” she said. “But just because you’re poor doesn’t mean you … don’t have the right to a quality education and the right to select the best education for your children.”

Garnica is a Democrat, and a loyal enough one for Gov. Jerry Brown to twice appoint her to a council on developmental disabilities. Her father, Alfredo Figueroa, was a United Farm Workers organizer who worked closely with Cesar Chavez. As a teen, she translated labor contracts into Spanish, and criss-crossed fields of melons and tomatoes to hand out fliers for pickets.

Yet she and her father make no bones about vouchers. They’ve pushed for them, and waited for them, for decades.

“Our students are locked into the system because of their economic status, and they can’t get out without vouchers,” Garnica told USA Today in 1993.

Garnica shrugged at the common perception that school choice is a creature of the right.

“We lived it first hand, so we know it’s not true,” she said.

There is no doubt, Garnica said, that Chavez himself was on board with creation of Escuela de la Raza Unida and, by extension, the bid for educational freedom it represented.

In a videotaped interview with Garnica’s father, Chavez talks about the need for the school, and for many more like it. (The interview can be found in this rough-cut documentary of events that led to the school’s creation.)

“The schools and the people who run the institutions want everybody to think the same way, and it’s impossible. We have different likes and dislikes, and different ideals, different motivations,” Chavez said. “And so I’m convinced more and more that the whole question of public education is more and more not meeting the needs of people, particularly in the case of minority group people … “

“Gradually,” he continued, “we’re going to see an awful lot of alternative schools to public education.”