This is the first post in our series on the Voucher Left.

It starts by condemning America for failing to provide equal opportunity in education. It ends with a knock on the war in Vietnam. Inbetween, it offers a template for a $15-billion-a-year national voucher plan that “will frankly discriminate in favor of poor children.”

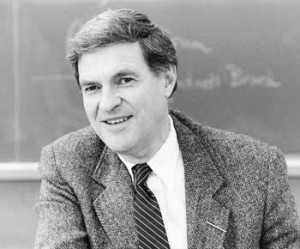

Published in 1968, “A Proposal for a Poor Childrens Bill of Rights” is a historical gem – a seminal document of Voucher Left history that remains curiously buried. It was co-written by Theodore “Ted” Sizer. Then dean of the Harvard Graduate School of Education, Sizer would become so influential and beloved an education reformer that 1,000 people would attend his funeral in 2009, including Massachusetts Gov. Deval Patrick.

Sizer’s Wikipedia entry doesn’t mention his embrace of school choice. Neither does his New York Times obit. But in the 1960s and ‘70s, he and other liberal academics like Christopher Jencks, Jack Coons and Stephen Sugarman were all promoting vouchers. They didn’t dismiss the market power underscored by Milton Friedman. But they also favored regulations that, in their view, would ensure low-income families had real power over education bureaucrats and real access to new education environments. Wrote Sizer in his manifesto:

Ours is a simple proposal: to use education – vastly improved and powerful education – as the principal vehicle for upward mobility. While a complex of strategies must be designed to accomplish this, we wish here to stress one: a program to give money directly to poor children (through their parents) to assist in paying for their education. By doing so we might both create significant competition among schools serving the poor (and thus improve the schools) and meet in an equitable way the extra costs of teaching the children of the poor.

Sizer likened his idea to the higher-education planks of the G.I. Bill. It differed from “conservative” K-12 voucher proposals in key ways.

Though the details are fuzzy, Sizer wasn’t talking vouchers for all, or vouchers just for private schools. (He doesn’t use the term “voucher” either, instead describing his proposal as a “supplementary grant.”) For political expediency, he thought half the school-age population should be eligible. And he suggested a sliding-scale for the value of the voucher, so the poorer the family, the greater the amount. (Berkeley law professors Coons and Sugarman proposed something similar in the 1970s, and tried to get it on the ballot in California. It attracted gobs of publicity, but ultimately failed to secure enough signatures.)

Sizer pushed back against the idea that vouchers were conservative. He struck back at critics who said they would “destroy the public schools.”

A system of public schools which destroys rather than develops positive human potential now exists. It is not in the public interest. And a system which blames its society while it quietly acquiesces in, and inadvertently perpetuates, the very injustices it blames for its inefficiency is not in the public interest. If a system cannot fulfill its responsibilities, it does not deserve to survive. But if the public schools serve, they will prosper.

Sizer wasn’t concerned with cost containment, or an expanded federal role in education. He thought a voucher worth three times the national per-pupil expenditure made sense, because he wanted an amount high enough to incent schools, public and private, to actively compete to serve low-income children. In raw dollars he proposed spending up to $1,500 per student per year, which, adjusted for inflation, translates to about $10,000 today.

In a 2004 interview with Education Week, Sizer suggested most contemporary voucher programs were too cheap to truly empower poor families. At the same time, he continued to emphasize the need for expanding options:

I favor a variety of schools. There’s no one best school for all kids. To get some variety, there should be incentives at the teacher and principal level, at the schoolhouse level, to create schools which clearly appear to serve the particular needs of an affected community. So, step number one is, families should be able to choose among those providers, among those schools, and carry with them a chunk of money that pays for that or pays for a significant portion of it.

In his 1968 essay, Sizer stressed that improving public education via vouchers wasn’t enough to remedy the ills of the poor. He wanted, as many progressives do, minimum wages, better access to health care and expanded welfare services. But as his son-in-law noted in an insightful essay after his death, there is more than one species of progressive, and Sizer’s was “the bottom-up progressivism of the urban reformer, not the top-down progressivism of the elitist technocrat.”

Sizer also made a case for choice as accountability, even if he didn’t use that term either. Parents make mistakes, he said, but he trusted them more than “the present monopoly of lay boards and professional schoolmen.” What was needed, he continued, was more power for parents, and a better balance of power between parents, teachers and regulators. Vouchers were a means to that end because they would “give to the poor some power to choose and control their own destinies.”

A few decades ago, other progressives thought this made sense, too.

Full disclosure: I work for Step Up For Students, which hosts this blog and helps administer Florida’s tax credit scholarship program, the largest private school choice program in the nation, and the state’s Personal Learning Scholarship Accounts program, its education savings accounts for students with special needs.

Coming tomorrow: Berkeley liberals and the roots of education savings accounts.